Emotional Maps of Oberhafen

Out and about with all five senses

by Beate Weninger and Petra Schlütter

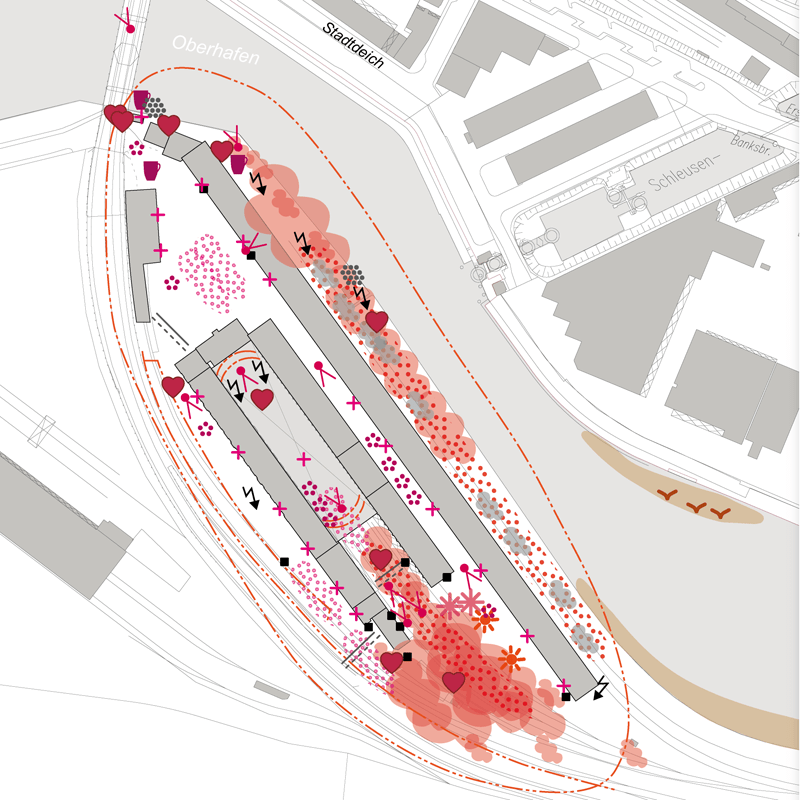

Is it possible to feel the spirit of a place with our senses and then record those impressions on a map without any given guidelines? And what happens when we lay several such maps on top of one another?

The Oberhafen is flooded with sunshine and it is cold and crisp as our workshop begins. On 2nd February, 10 men and women of all ages explore the area of the Oberhafen and mark their subjective impressions on a schematised map.

We, geographer Beate Weninger and political scientist Petra Schlütter, followed up questions on the specific qualities of the Oberhafen posed by people interested in the project. As a result of the workshops, this type of questioning has become part of our vision for the Oberhafen. To find out what the true spirit of the place is like we decided upon a radical, subjective approach.

In the Oberhafen e. V. “playroom” in the main building on the Oberhafen premises – a bright, white room – the results of our fieldwork, individual maps, were hung up on a wall and analysed. We present the impressions gained from intercommunication, based on report notes and our memories. Both sensory impressions and emotional perceptions are recorded.

Emotional Map of Oberhafen, PDF →

Results of the field visits

Kinaesthetic impressions: touching, walking, smelling

Nearly all participants notice the change of light and shade, and warm and cold as they pass through the various zones of the Oberhafen grounds. They stress the positive experience of being able to go outside in the sunshine in February, which through temperature changes in the different “climate zones” becomes a joyful event.

The participants describe the topography in terms of contrasting variety. Up on the tracks, the slope to the left and right, different levels and steps and ramps on the premises. While walking different levels are mastered and considered to be worth noting along with the differing textures of the ground under our feet – new thresholds make a transition to further spaces possible. Change is the distinguishing element.

The nose (olfactory level) plays a part; particularly around the Oberhafen cantine there is the smell of food, which is positively recorded; in other places it smells of something burning, making one wish to be some place elsewhere.

Aural impressions: our ears are always open

The next stop is a visit to a place quieter than the surrounding city, at least when no trains are passing. The echo of one’s own footsteps on different kinds of paving stones is noted. The sudden silence and withdrawal from the loudness of the city, like being on an island is impressive.

Visual impressions: we look and look

The play of light and shade arises from the light and dark areas between buildings and through some of the see-through roofs of the sheds – one associates it with being both sheltered and transparent at the same time.

The participants describe the new perspectives now opening up; the long visual axes along the train tracks and between the sheds; the expanse to the rear on the tracks and on the waterfront; and at the same time a restricted perspective – viaducts with their sections. The view is often divided into two: by walls and buildings with an industrial background and by the expansive sky above. Then there is the view of the city when one looks in the other direction, opening up a beautiful new perspective.

Colour impressions come from nature bursting through (the light green of the birches between the train tracks, mullein and bushes) and the perception of building surfaces and other objects (earthy brown, facets of blue, colourful graffiti, blue water), but are downstream of their depictions. They serve more to illustrate emotions. The view of building surfaces is similar too; the partly rough surfaces due to masonry recesses and traces of decay testify to a time gone by.

Sensations: heart, soul and spirit begin to vibrate

Emotional impressions beyond pure sensations are mentioned. The contrast in noticeable between cosy, sweet, safe (Oberhafen cantine) and eerie (overgrown area in the direction of the water edge, difficult to walk on) or inhospitable (only warehouses). Most often noted is the contrast between the tracks and warehouses, metal and asphalt, concrete pavements and desolate places where nature is fighting back. The deserted “wilderness” shows up repeatedly as a theme, which begins behind the sun-terrace (behind Lands End) and is for many a favourite spot – partly because of tracks disappearing into the distance. The unplanned green is felt to be calming and is verbalised. Abandoned and bustling – unplanned, strengths of nature, and industrial buildings with signs of wear and tear show an appealingly felt contrast.

For some, the smoky walls in the grounds awake childhood memories, for others, the richness of the shades of brown in the walls remind them of their homeland. To contrast abstract terminology such as left and right, other sensory reference values are used. The room is navigated by using definite objects.

The spirit of the Oberhafen originates from the contrast of the territory.

From our point of view, the “spirit of the place” is about the contrasts and changes in the area – about a compact juxtaposition of differing sensory qualities, which can be experienced at the Oberhafen.

In the closing discussion about what needs to be preserved at the Oberhafen, it is evident that the place’s history (descriptions of the train tracks, which should definitely be retained, are dominant here), and the visual structural testimonies to times gone by are unmistakeable qualities, which have led to the place becoming what it is today.

With the surrounding water and quay wall on the one side, and the viaduct and gateway-like entrance on the other, it is this tangible limitation, contrasted with long views and wide expanses of sky (due to the low buildings) which makes up the Oberhafen: limitation and vastness at the same time.

Just as important is the visual juxtaposition of the still existent storage facilities and places which have been completely left alone: workplaces dedicated to specific activities and other arbitrary places are a further example of contrasting terms.

References and penetrations

The opening of the inner world and the emergence of the place’s magic are made possible by the sum of sensory impressions and in particular the variety in such close proximity. In its present condition the place is neither formed purely by human hand, nor is it completely wild. Both permeate in certain areas due to materials, which have become crumbly with time. Establishing a connection can be helpful, culminating in the area described as a sun-terrace adjacent to a wilderness. This allows a view into the distance; from the man-made terrace on the threshold to nature, a picture of self-sufficiency.

The Oberhafen is in the middle of the city and an inviting, nostalgic place. It doesn't overwhelm its visitors as nothing it too big or too far away, but it gives them the space to submerge themselves, in a free-thinking, playful way, in the sensory experience of a place – a wonderful prerequisite for creativity.

What does this mean for further development of the area?

In addition to further development of the area; piece-by-piece repossession and creative use of the original raw materials, the Oberhafen also needs areas left to grow wild without any interference. What could be more provocative and productive than such a well-defined neighbourhood of creative re-loading points alongside nature in all its self-sufficiency?

In contrast to the relatively uniformly developed neighbouring area, the Hafencity; to the museum-mile along a long transport axis; and to the large structure of the former market, it is the diversity of the micro-spaces at the Oberhafen which makes it so interesting and touching. There is room for all five senses at the Oberhafen on a completely different wavelength compared to classical cityscapes. This spirit needs to be preserved and nurtured.

We would like to thank the Oberhafen e. V. for their kind support with the workshops and to Micha Becker for the map.

We thank Rebecca Lenton for her accurate translation of this text into English.